- Home »

- Insights »

- Global CIO View »

- Macro »

- Deglobalization – rather diversified globalization

For a long time globalization came down to just two points for economists: companies benefit from lower input costs and new markets; consumers benefit from lower prices. The political appraisal has always been more complex. The hope that global trade, embedded in multilateral rules, would make military conflicts less likely was contradicted by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. But it had become apparent long before that countries tend to decide against the economically most sensible alternative, and sometimes to a drastic degree. In industrialized countries the previously underestimated political consequences of globalization became apparent for all to see with Brexit and the election of Trump. What emerged above all was the disappointment of those who saw themselves as losers from globalization.

This does not help multilateralism. The trade war between China and the U.S. has further weakened the World Trade Organization (WTO). Bilateral agreements are gaining importance, supply chains are being reorganized, and trading partners are being reselected as countries seek others who share a similar value system. National security is again more frequently cited as a reason for or against a trade partnership. This usually makes exporting more complex, and in purchasing the most favorable suppliers can be eliminated.

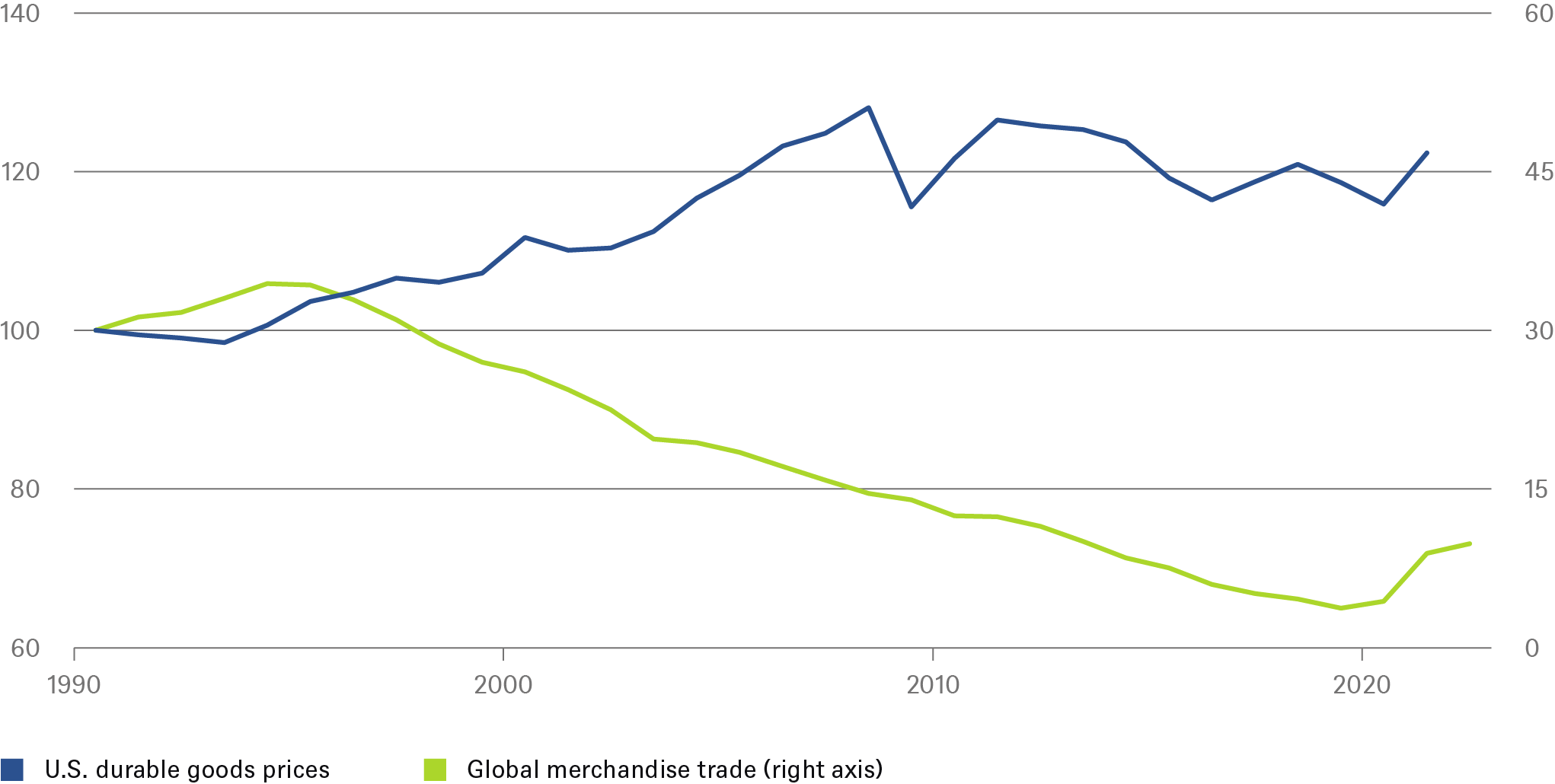

Merchandise trade vs. durable goods prices

indexed: 12/31/90 = 100% of GDP

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 12/31/22

This trend was accelerated by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. Greater autonomy and secure access to critical goods were prioritized over short-term cost minimization in procurement and production. This affects structurally important products: energy, rare earths, pharmaceuticals, defense, high technology.

As the chart shows, globalization hit its peak in 2008 and was then temporarily dampened by the financial crisis. Even after a recovery period it never reached the pre-financial crisis trend, but rather continued to lose momentum from 2011 onwards. Still, we think it would be a mistake to say globalization is over. We prefer to speak of a diversified (or regionalized) globalization, for several reasons.

First, the advantages of the global division of labor and of large markets are too compelling for companies. Second, no region is self-sufficient and thus able to do without global trade. Third, global trade in data, services and intellectual property is increasing. Between 2010 and 2019, international data exchange grew by 45% p.a.[1] and trade in services and intellectual property grew by about 5% p.a., (vs. trade in goods at 3% p.a.). Fourth, we believe that foreign trade policy in Europe and the U.S. is increasingly taking into account voters’ concerns, which could lead to greater acceptance of global trade agreements. The reorganization of supply chains that is taking place is likely to drive costs in the short term. In the longer term, however, benefits (such as greater certainty on planning, for example) are likely if trading partners have been chosen more carefully.

In general, one should not underestimate companies’ adaptability. Look, for example, at how they have dealt with skyrocketing energy prices in Europe. But one thing remains the same: globalization is too complex to allow for any quick conclusions about its fate.