For political aficionados, one prediction can safely be made already at the outset of 2020: it promises to be another bumper year full of excitement. In such an environment, it seems quite likely that markets will occasionally take fright, whenever an emerging apparent trend catches them by surprise. Old hands on Wall Street, however, recognize that it is far too early to assess which, if any, major policy changes might be in the offing beyond 2020. Indeed, a good, initial approach – at least until Labor Day 2020 – might well be not to get carried away by political headlines.

For political data nerds like ourselves, the task is somewhere in between: It is telling what signals to listen up for in all the noise in the coming months. And it starts with briefly looking back at 2016. In addition, we assess U.S. polling, take a first look at what else may be at stake, share our favorite sources of information and provide our own probabilistic assessment on three market-relevant types of outcomes. And, if that is still not enough to sate your appetite for political forecasting, we conclude with a reading suggestion likely to serve you well in 2020 and beyond.

1. The meaning of 2016

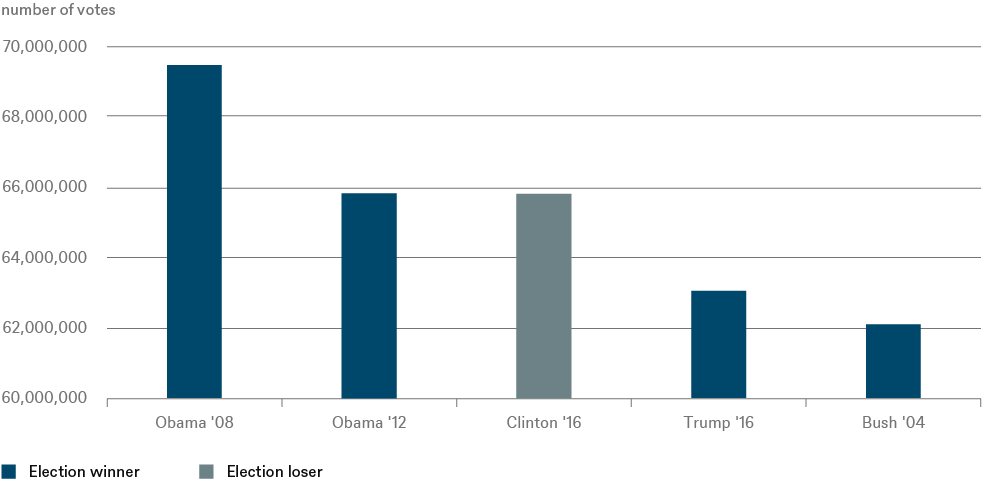

Statistically speaking, Trump can be classified very much as an accidental president. In Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, the three states that propelled him to victory in the Electoral College, he was ahead by a mere combined 78,000 votes (or 0.56%) out of 14m votes cast in those states.[1] We will take a more detailed look at the Electoral College starting in Section 3. In the meantime, it's important to start by recalling how narrow Trump's path to victory was in 2016, compared to winners in previous contests.

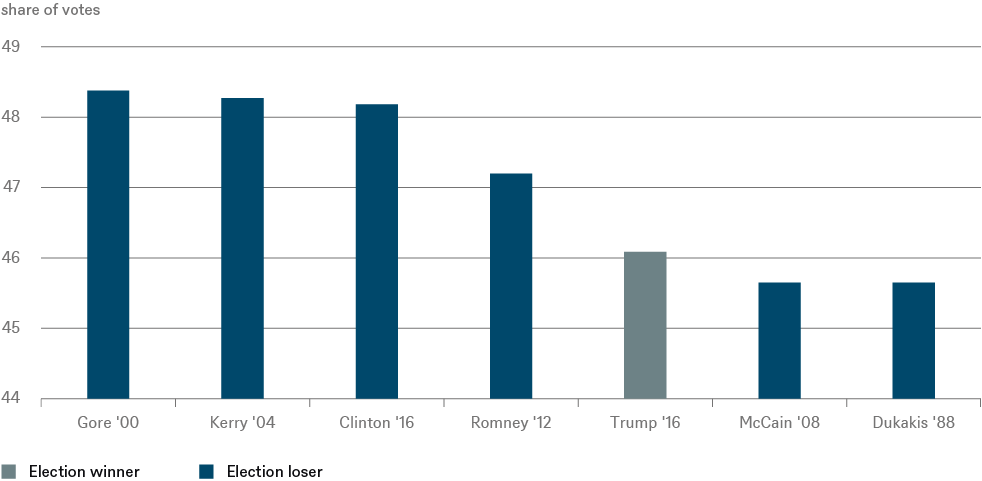

Looking back at all presidential elections since 1984, the average winner garnered 50.3% of the popular vote. Between 1984 and 2012 (i.e. excluding 2016 and Donald Trump himself), the average winner's vote share was 50.9%, i.e. only marginally higher. Trump received 46.1%, despite the absence of strong third-party candidates (such as Ross Perot in the 1992 and 1996 presidential elections).

Chart 1: Popular-vote share in U.S. presidential elections since 1984

Winners' shares delineated in orange. Dashed line marks the average winning percentage of 50.3%

Source: Federal Election Commission as of 12/19/19

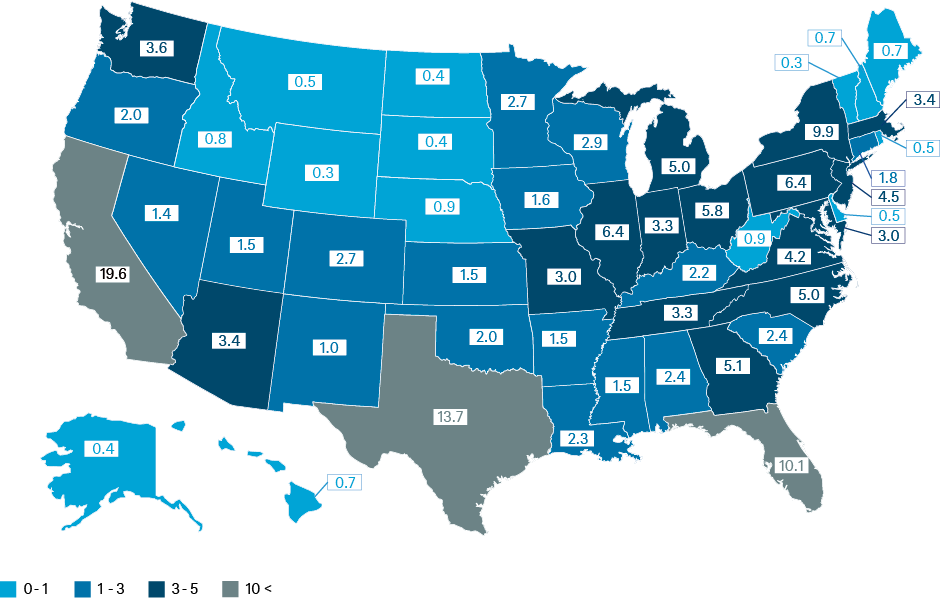

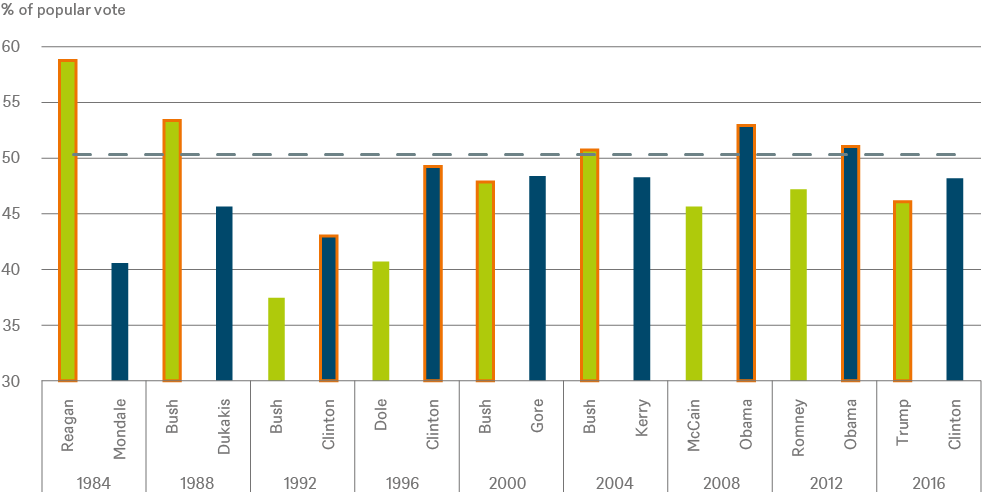

Not that Hillary Clinton was doing all that much better as a vote getter than Trump. As we described in our 2016 CIO View Special, both Mr. Trump and Ms. Clinton had historically low favorability ratings.[2] To paraphrase the old saying, both 2016 candidates arguably managed to come in third or fourth in a two-horse race. Trump's share of the vote was barely higher than that of Michael Dukakis in 1988 – and below that of the losing candidates in four of the last five presidential elections (see chart 2). And, despite population growth, the number of votes for both Clinton and Trump in 2016 lagged behind Obama's 2012 and well behind Obama's 2008 vote totals (see chart 3).

Chart 2: Losers and Trump

Chart 3: Winners and Trump

Source: Federal Election Commission as of 12/19/19

So what, you might well ask. Trump still won 2016. The trouble is that the way he won raises serious doubts about how much to read into his victory for 2020. Back in 2012, conservative commentators were keen to point out that incumbency by no means guarantees re-election: "History shows that whenever once-elected presidents seek a second chance, more often than not the people say no."[3] As with any verdict electoral "history" delivers, we would urge some caution, especially when "history" is viewed through partisan lenses.

Other than Trump, there have only been 3 instances since the American Civil War in which the Electoral College winner did not receive the most votes in the general election (1876, 1888 and 2000). Among these previous "popular-vote losers," only George W. Bush was able to win re-election (and he had only lagged by a modest 0.5%). So, it's hard to say how much to read into that 2016 victory for 2020. Trump's victory in 2016 is arguably unprecedented in modern times. This is not just because Trump was an unusual candidate, with an unusual voting coalition. How Trump voters were geographically distributed was critical to his success in the Electoral College.

At least part of the reason incumbency was helpful for a candidate like Obama in 2012 is that he could afford to lose plenty of voters (almost 3.6 million, as it turned out) and still comfortably win re-election. Trump, by contrast, has no such margin for error. We return to what all this might mean for forecasting purposes in Section 5.

2. U.S. polling and how to think about Trump's chances of getting re-elected

At the time of writing, the impeachment process is still unfolding in the Senate. For forecasting purposes, we see the Senate trial as a bit of a side show. It remains very unlikely that enough Republican Senators (who control that chamber with 53 out of 100 votes) will consent to convicting and removing President Trump from office.[4] And while it is possible that some swing voters might see impeachment as a stain on his performance, it is at least equally plausible that the Senate trial might help Republicans consolidate and mobilize their base in November.

It's even possible that both things might happen at the same time, with the politics playing out differently on the ground in different parts of the country. Something similar happened ahead of the 2018 midterm elections, following the acrimonious Senate hearings of Brett Kavanaugh for a seat on the Supreme Court. The ensuing controversy over sexual-assault accusations came at a critical point of the campaign. It simultaneously appeared to contribute to Republicans consolidating and turning out their base in key Senate races and to the problems Republicans faced in retaining female supporters in suburban House districts.

Or, of course, other events such as escalating tensions in the Middle East, might leave impeachment a distant memory for most voters, come November. In any of these cases though, there will most probably be plenty of time for such patterns to become more clearly visible in the polls, much as they were after the Kavanaugh controversy.

The state of U.S. polling in general is also an important consideration in thinking about how to interpret new information in coming months. As we wrote ahead of the mid-term elections of 2018: "U.S. elections are quite unusual in that you have a wealth of historical data, plenty of high-quality pollsters and a vibrant community of data-driven analysts and commentators. A data-driven, probabilistic approach to predicting and analyzing electoral outcomes was pioneered by Nate Silver and https://fivethirtyeight.com/. Quite a few others have embraced a similar approach. That is one of the reasons covering U.S. elections is both easier – because we have to do less number crunching ourselves – and more fun – because there are plenty of knowledgeable commentators."[5]

Three key articles of faith among those U.S. commentators are that, first, even high-quality surveys can suffer from polling errors of unknown magnitude and direction. (When such misses happen, they tend to reflect methodological choices and biases in the raw data used, rather than random sampling errors). Second, averaging large numbers of polls and weighting polls to reflect both sound methodological choices and forecast accuracy in past elections can mitigate against this risk. It also provides valuable insights into how large polling errors have been in the past, and whether polls in general for any particular type of race have gotten better or worse. Third, though, it is widely seen as a mug's game to try to guess either the magnitude or the direction of a suspected polling error in the U.S. context.

For all political forecasts we have been doing around the world, we broadly subscribe to articles one and two. But we tend to be a bit more agnostic than our U.S. peers when it comes to their third article of faith: the idea that you should never be in the business of trying to guess both the magnitude and the direction of ways in which a country's pollsters might be getting things wrong. We agree that trying to "unskew" U.S. polls is generally a bad idea, for reasons well explained by CNN analyst Harry Enten a few years ago.[6]

However, our experience outside the U.S. suggests that in countries where much of the polling is truly dodgy, cautiously second guessing the pollsters can improve forecasting performance. For example, in Italy, most polls have been notoriously unreliable for many years. In others, such as the UK and France, there are good reasons to think that polling has gotten harder, making purely polling-based forecasts less reliable than they used to be. Based on such experiences, we are a little more willing than our U.S. colleagues to occasionally go out on a limb, especially when there are tentative hints in at least some polling data or recent electoral events of what might be going wrong.[7]

Occasionally, that may even be appropriate in the U.S. For example, the Democratic win in the 2017 Alabama Senate race offered an indication of how most pollsters had been underestimating the extent to which the Trump presidency would boost turn-out among Democratic leaning groups, notably younger voters.

The snag is that U.S. pollsters usually pick up on such trends before too long. You can see this quite clearly in the helpful analyses of polling accuracy and signs of partisan bias Nate Silver publishes every few years. Up until now, the results have invariably tended to indicate that: "Poll Averages Have No History of Consistent Partisan Bias (…) the historical evidence suggests that it is about equally likely to run in either direction"[8] (as of 2012); and that (as of 2018) "The Polls Are All Right (…) Over the past two years — meaning in the 2016 general election and then in the various gubernatorial elections and special elections that have taken place in 2017 and 2018 — the accuracy of polls has been pretty much average by historical standards."[9] In fact, "the 2017-19 cycle was one of the most accurate on record for polling. (… In 2017-19) polls had essentially no partisan bias, and to the extent there was one, it was a very slight bias toward Republicans (0.3 percentage points). And that's been the long-term pattern: Whatever bias there is in one batch of election polls doesn't tend to persist from one cycle to the next."[10]

All of which suggests that in 2020, U.S. polls should be taken seriously. Indeed, loudly stated distrust of polling in general among many pundits is quite a good and reliable indicator of which pundits you may be better off ignoring. To put it bluntly, we believe those pundits who gave up on polling in the aftermath of 2016 generally don't know what they are talking about and still haven't bothered to find out. Read them for entertainment, if you wish, but you might not want to rely on them when considering investment or any other decisions that require forecasting skills.

For forecasting purposes, we believe a better one-stop source in the U.S. is FiveThirtyEight, which has built up a solid track record over different cycles and races. Of course, that does not mean their – or any other – poll-based analyses and forecasts will always get it right. Indeed, we will probably highlight quite a few of our favorite sources in the course of this campaign, as well as our own areas of disagreement with consensus forecasts. Nevertheless, we suggest keeping an occasional eye on FiveThirtyEight. If you only want to follow one or two indicators to cut through the political noise, the first that you might want to look at is the FiveThirtyEight Trump approval and disapproval tracker, available at: https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/trump-approval-ratings/?ex_cid=rrpromo.

Helpfully, this tool also allows checking how Trump's numbers compare with past presidents at this stage of the presidency. To some extent, re-election battles are always a referendum on the incumbent's record, not just a choice between different visions for the future. Trump's numbers suggest that both he and other Republicans might be vulnerable. After all, much more is at stake in 2020 than just the presidency.

3. The Senate, the House and the Electoral College

In 2018, Republicans lost their majority in the House of Representatives, but made a net gain of two seats in the Senate.[11] The result, once again, was a divided Congress and, therefore, a divided government for the last two years of Trump's first term in office. As we pointed out in our 2016 CIO View Special from which parts of this paper are adapted, America's founding fathers were assiduous in avoiding any one person or branch gaining too much power. Hence, the emphasis on checks and balances.

The idea behind having two chambers was that representation in the House should be based on population. By contrast, six-year, overlapping terms in the Senate would act as a brake on rash schemes. Having two Senators each would also ensure that small, less populous states could make their voices heard in Washington.

Some quirky features of democracy in AmericaIn the U.S. electoral system, oddities abound. Long before the Trump era, the world was reminded of that in the 2000 election, when Al Gore won the popular vote, but ultimately lost the Presidency after the Supreme Court stopped a recount in Florida. Most states award electors on a “winner-takes-all” basis through the Electoral College, which chooses the President and the Vice President. (The exceptions are Maine and Nebraska, where some electors are picked at the level of congressional districts.) Casual observers might be less familiar with some other quirks of the U.S. political system. In particular, the number of electors in the Electoral College is based on the total number of Senators and Representatives. Since each state – no matter how small its population – has at least one Representative and two Senators, each gets at least three electors. It is worth keeping in mind, though, that the rural bias is quite small for the Electoral College as a whole and can potentially benefit either one of the two big parties. The vast majority of its 538 electors come from states with large populations, with California (55 electors), Texas (38), Florida and New York (29 electors each) having the most sway. Of course, the impact of this federal structure and rural bias is much larger when it comes to the legislative process than it is in the Electoral College. Currently, seven out of 50 states have only one Representative (as well as the standard two Senators): Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont and Wyoming. And, as below chart shows, there are plenty of other small or sparsely populated states with fewer than one million residents per U.S. Senator. Resident population in millions per U.S. Senator

Source: United States Census Bureau, DWS Investment GmbH, as of 9/8/16

Each Senator from a state like (tiny) Vermont, say, has just as much voice as the Senators representing the most populous states, such as California, Texas or Florida. In particular, he or she can dramatically slow down proceedings by withholding unanimous consent. This contributes to the impression of gridlock in Washington. As for Washington, D.C., America's capital has no voice in the Senate because it is not a state. It does not even get to run its own affairs. It does get to send non-voting delegates to the House and has three electors in the Electoral College. |

In 2020, all 435 seats in the House of Representatives and 35 of the 100 seats in the Senate will be up for grabs. So will 13 state and territorial governorships, as well as plenty of seats in state legislative chambers. Those state-level elections are consequential too for federal politics.

Party control at the state level will largely determine how Congressional maps for the House of Representatives are redrawn following the 2020 United States Census. Whenever they are in control, both parties have historically tried to ruthlessly gerrymander House districts to maximize their overall electoral advantage. Since the 1980s, better and cheaper mapping software has also made it increasingly simple to manipulate congressional district maps. The results are House districts whose geographic shape defies logic – and more and more Representatives elected in increasingly partisan districts. Such parliamentarians have little to fear from the general election – but everything from primary challenges from within their own party.

Since the 2010 Census, House district maps have generally worked in favor of Republicans, who controlled most state legislatures at the time of the last round of redistricting.[12] Court challenges of those maps have somewhat reduced this source of Republican advantage in recent years. In the 2018 mid-term elections, Democrats won 235 seats or 54% of House seats on a 53.4% share of the national vote.[13]

Defending a seat is generally easier than winning it in the first place. Incumbent members of the House benefit from wide name recognition (after all, they have run before) and usually have an easier time than their challengers in raising campaign funding. Despite the advantages of incumbency, Democrats will probably need to do somewhat better than Republicans in terms of how many votes their candidates get to retain control of the House in 2020. Gerrymandering can explain only part of the likely Republican advantage. Another factor is how concentrated Democratic votes are in urban areas. According to most estimates ahead of 2018, Democrats needed to win the popular vote by about 5% to 7% to win a majority in the House of Representatives.[14] For 2020, we think that a lead at or even slightly below 5% in national vote shares would probably suffice. But the lower it gets, the more the resulting Democratic seat count will likely depend on how those votes are geographically distributed, putting the Democrats' House majority in danger.

If they manage to win in 2020, Democrats stand a good chance of enshrining their majority in the House for quite a while. The next round of redistricting will take place in 2022, and compared to 2010, it is already clear that their political fortunes have markedly improved at the state level.[15] In a good year at the federal level, they might of course do a lot better still. That will partly depend on who Democrats end up nominating.

4. Three types of outcomes and how and when to re-assess their probabilities

When making probabilistic forecasts, there are often trade-offs between which types of scenarios may be useful for tracking forecast accuracy and which ones people may actually be interested in. For example, our initial U.S. election probabilities which we started introducing internally a few months ago has just three clearly identifiable scenarios for the presidency. We currently see a 40% probability of Trump being re-elected. Our other scenarios are: a Democratic challenger wins (50%) or another Republican or third-party candidate wins (10%). We initially introduced that 10% bracket to capture both the – at the time fairly distant – impeachment prospect, as well as Trump potentially deciding not to run again for health or other reasons.

For investment purposes, that is not all that useful. Effectively, it amounts to saying that the 2020 presidential election is close to a toss-up, with Democrats enjoying only the tiniest of edges compared to Republicans. We will explain why we think so in Section 5.

Moreover, our Trump re-election forecast does not tell much about which policies the next president will be able to pursue. That partly depends on how both parties will do in Congressional elections. Our initial U.S. election scenarios do have some advantages we will turn to in Section 5.

In parallel, though, we are introducing three slightly more user-friendly types of potential outcomes today. Think of them as a representative sampling of all the overall 2020 electoral outcomes you may want to currently consider when making investment decisions:

-

Trump Triumph: President Trump wins re-election and Republicans win in both Houses of Congress, to which we currently assign a 20% probability. For markets, that might mean tax cuts are back on the agenda. Deregulation could continue unimpeded. But so too might the potential for further trade tensions.

- Mushy Middle: This set of outcomes is typically epitomized by various combinations of a divided government and has an overall 65% The precise outlines of any such combination could have big implications for individual sectors. For example, imagine that Republicans hold on to the Senate, but lose the White House. For political aficionados and fracking businesses alike, there is obviously a world of difference between the current status quo of a Republican president facing a Democratic House of Representatives, and, say, the prospect of a newly elected President Joe Biden rolling back Trump-era deregulation measures. But, at least in the months leading up to Election Day, the prospect of such an outcome is likely to be relatively neutral for financial markets overall.

- Progressive Pop: The Democratic nominee wins the presidency on a far left, progressive policy platform and Democrats take back the Senate as well as retaining control of the House. We currently assign a 15% probability to such an outcome. That prospect certainly has the potential to scare markets. As we will see, moreover, it is highly likely that at some point of the campaign, markets might be rattled by this apparent danger.

From a market perspective, this way of thinking may allow you to tune out much of the noise surrounding U.S. politics, probably until the campaign starts in earnest around Labor Day 2020. Until then, in our view, there are only two key questions to consider when thinking about any event. Does it significantly move the needle towards outcome "a" of a Trump Triumph? Or might it increase the probability of a Progressive Pop, our outcome "c," that the Democratic nominee wins the presidency on a far left, progressive policy platform and Democrats take both the Senate and the House?

Moreover, you probably won't need to listen to 24-hour cable news coverage to find out in time and take into consideration portfolio adjustments. For outcome "a" of a Republican sweep, we are reasonably hopeful that just two indicators will tell you much of what you need to know. We have already mentioned the first one, namely Trump approval ratings.[16] Historically, presidential approval ratings have correlated well with the fate of incumbents, come November. The same is true of the second indicator, namely the congressional generic ballot, again using a FiveThirtyEight tracker: https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/congress-generic-ballot-polls/. It asks voters which party they support in a congressional election, without mentioning specific candidates. This neatly sums up how favorable the general climate is for either party. At the same time, it tells you how much of a chance Republicans might have of winning back the House. As a rough cut-off point, we would suggest watching out for the Democrats' lead in the congressional generic ballot to fall to five percentage points or less.

Such a signal would be especially noteworthy if it coincided with President Trump's approval ratings rising and staying at or above 45% in quality-weighted polling averages nationally. Together, we think these two trackers can go a long way in deciding whether and when to re-assess the likelihood of Republican wins across the board along the lines of the 2016 results. Of course, even such Republican improvements in polling trends would not guarantee victory. For reasons explained in Section 5, Trump's path in the Electoral College will probably remain exceedingly narrow, unless and until he somehow manages to get his approval numbers close to or above 50%. Based on current data, our 20% probability for outcome "a" is arguably a touch high. It partly reflects that it is still early in the campaign. A lot can still happen and President Trump will at least partially control the agenda. If his poll numbers improve, our interpretation of the data will partly depend on context and also how far the campaign has advanced.[17] But assuming that he does win re-election, it is not that implausible that Republicans would also win back the House on his coattails.

One further advantage of keeping an eye on the congressional generic ballot and Trump's approval ratings is that it also furnishes many of the ingredients needed to assess the likelihood of a Progressive Pop, our outcome "c." To recall, this corresponds to the Democratic nominee winning the presidency on a far left, progressive policy platform and Democrats having control of both the House and the Senate.

We currently assign a 15% probability to such an outcome. There are three reasons why we see such a left-wing takeover to be a fairly low-probability event:

-

First, the eventual Democratic nominee would need to be someone who decides to / wants to run on a far left / progressive platform. At the time of writing, this appears most plausible if Senator Bernie Sanders were to win the nomination. After all, Sanders is not even a Democrat, but a self-described Democratic Socialist. It is of course quite possible that a candidate other than Sanders pivots to the far left. Based on her positions and voting history, this seems especially plausible if Senator Elizabeth Warren were to win the nomination. However, her chances have recently been fading.

-

Second, whoever the nominee is, he or she would need to have enough delegates to get that platform passed by the Democratic National Convention[18], without having to reach out to moderates. Resistance against such a takeover of the Democratic Party – let alone the whole country – remains strong, and not just in Democratic-Party circles. This was clearly evident in the debates so far during the Democratic primary process, when it comes, for example, to providing government-run healthcare or free college tuition for all. Such goals have been endorsed, to varying degrees, by Senators Warren and Sanders, but are fiercely opposed by most of the other candidates.

-

Third, and finally, such a progressive platform would need to be sufficient for Democrats to be so electorally successful in November 2020 that they also win Congress and are able to implement their agenda. At the time of this writing, that is still very much in doubt. Moreover, there would be quite a risk of more moderate Democratic lawmakers resisting such efforts in Congress, or even abandoning the party all together.

The third obstacle to a far-left takeover is intimately related to the broader political backdrop, captured by the congressional generic ballot and Trump's approval ratings, or even more specifically Trump's disapproval ratings. Plainly, the more unpopular Trump and other Republicans are, the easier it is to imagine voters opting for a radical alternative. However, we are somewhat doubtful it will come to that.

Polls suggest that about two-thirds of Democratic-primary voters would prefer someone who can beat Trump to someone who "agrees with you" (i.e. the voter being polled).[19] That has been a key reason for the resilience of former Vice President Joe Biden, the rise and fall in the poll ratings of young Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg, recent improvements of Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar and the steady rise of Mayor Michael Bloomberg since his late entry into the race. All of them are keen to present themselves as centrists, notably on economic issues. The interest in beating Trump and staying on a fairly centrist course also appears to be shared among party elites. And, as political scientists John Zaller, Hans Noel, David Karol, and Marty Cohen argued in their influential 2008 book, "The Party Decides," party elites, from fellow politicians to donors and media pundits, have historically been quite influential in shaping primary results for both main parties. As a result, the winner is usually one of the candidates thought to be able to succeed in the general election, while at the same time being more or less in sync with party opinion.[20]

Of course, primary campaigns are partly tests of what the party opinion is on any given issue. They can also provide tentative clues of how likely an outsider candidate may be to succeed in the general election. Back in 2016, Donald Trump made opposing free trade one of his unique selling propositions. That put other candidates in a difficult spot when trying to make a credible counter offer to voters without losing business support. Trump was appealing to a certain type of Republican base voters, which had been neglected by his rivals and other office holders. This, in turn, provided valuable (and widely ignored) pointers to how he would perform in Midwestern states that narrowly swung towards Trump in the 2016 general election, giving him a substantial lead in the Electoral College.

Mindful of that experience, we suggest that the third item worth watching, once the Democratic primaries start, is the tally of state-level results for left-leaning Senators Bernie Sanders and Elisabeth Warren. We will look out for how the total of left-leaning Senators Sanders and Warren compares to the percentage shares Sanders alone won in each primary state in 2016, when facing Clinton. Of particular interest in assessing the likelihood of outcome "c" of a Progressive Pop will be how these two progressive candidates fare in the Midwest and other swing states, particularly those with open primaries. That could provide valuable pointers on how a shift to a more progressive policy platform might impact the prospects of both parties in the general election.

Keeping such a tally is also likely to mitigate what we would see as quite a likely risk event to hit at some point in coming months. Our impression is that among Wall-Street colleagues, the chances of Trump winning re-election are probably being overrated. The same is perhaps true of Mayor Bloomberg. Despite his recent climb, he is still only polling at about 6% in national polls among Democratic primary voters. For any "normal" candidate, that would be far too low to be taken very seriously. Then again no previous U.S. presidential candidate had Bloomberg's advantages, including his vast fortune and ownership of one of the world's leading news organizations. Still, his path to winning the Democratic nomination looks pretty murky.

Moreover, markets may be ill-prepared for the all-too-predictable storyline of one or a few upset victories for left-leaning candidates reshaping the race. We say predictable since unlike presidential general-election polls, primary polls are often wide off the mark. According to analysis of the data since 2000 by FiveThirtyEight, the average polling error in all presidential primaries has been a whopping 8.7 percentage points.[21] In such a fluid field, electoral upsets are highly likely. Some of them will probably involve Senators Warren or Sanders doing much better than expected in certain places.

Comparing their combined tally to Sanders' percentage vote share and delegate count in 2016 should help to avoid reading too much into what might turn out to be state-level outliers. Hopefully, however, it would also provide a timely pointer to Senator Warren's wealth-tax proposals, for example, being more of a vote getter than pundits think in the Washington beltway.

5. Some final thoughts and a reading suggestion

As promised above, there are a few loose ends left to be tied up. We argued in Section 1 that Donald Trump's 2016 victory was quite unconvincing by historical standards, suggesting vulnerability. In Section 4, however, we mentioned that the 2020 presidential election is close to a toss-up, with Democrats enjoying only the tiniest of edges compared to the Republicans. The main reason for this discrepancy is the Electoral College.

At this stage of the campaign, we think that the most reasonable way to think about the Electoral College is that it massively increases uncertainty in both directions. In our view, it is premature to say which party might benefit from this way of choosing a president in 2020. Like polling errors, the fact that it has favored one party or candidate in one election does not necessarily tell us all that much about the Electoral-College landscape in the next one. More often than not, those preconceptions turn out to be wrong. "The speculation before the 2000 election was that Mr. Gore might win the Electoral College despite losing the popular vote – exactly the opposite of what happened."[22] In 2004, the Electoral College instead did favor Democratic candidate John Kerry, who got into spitting distance of winning the presidency, despite lagging Bush by more than 2% in the popular vote. Similarly, in 2012, Obama did much better in the Electoral College against Mitt Romney than his relatively slim 3.9% popular-vote edge would have suggested.[23] And as we pointed out before the midterm elections in 2018, "[…] remember how in 2016 the Electoral College was supposed to provide Hillary Clinton insurmountable advantages? That was correct in the limited sense that using the 2012 presidential-election results as your starting point, Clinton appeared to have plenty of routes for a majority. Her floor in the Electoral College also appeared to be quite high. By contrast, there were only a comparatively limited number of paths to victory for Trump."[24]

Without knowing who both major parties end up nominating, it is very hard to say which particular Electoral College map of the years mentioned above is likely to serve as the best template. Moreover, Trump's low approval numbers, well below 50%, add an additional element of uncertainty, even if his eventual rival ends up to be as unpopular as Clinton was in 2016. One interesting feature of 2016 that many U.S. observers appear not to have fully taken onboard is the critical role third-party candidates played in this vote and precisely why the contest was so much harder to call "correctly" than in 2012.

In 2012, the winners in all 56 Electoral-College contests (i.e. in the 48 winner-take-it-all states as well as in Washington D.C. and in the congressional districts in Maine and Nebraska where some Electoral votes are assigned on the district level and some at the state level) won with more than 50%. (The tightest contest was Florida, which Obama carried with 50.01% vs. Romney 49.13%.) For any given voter, knowing everyone else's voting intention would not have changed the results. It generally made sense for each voter, to vote his or her "true" preference among the available options.

In 2016, by contrast, 15 contests went to a "winner" of less than 50% of votes within those states or districts. Those contests accounted for 157 electoral votes out of 538, i.e. easily enough for an Electoral-College "landslide" of either Clinton or Trump. In those 14 states, as well as Nebraska's second congressional district, both Trump and Clinton were so unpopular that enough voters decided to instead vote for independent or third-party candidates to deprive them both of a 50% win.

In most places, those votes were pure protest votes, in the sense that none of these third-party candidates had any realistic prospect of winning an Electoral-College vote, let alone the presidency. One interesting exception was Utah, where anti-Trump Republican Evan McMullin ran as an independent candidate with an outside chance of carrying that state. The final Utah result was 46% for Trump, 27% for Clinton, 22% for McMullin and several other candidates accounting for the rest. This example nicely illustrates why 50% is considered such an important threshold in many electoral systems. Theoretically, there were enough Clinton and McMullin voters to deprive Donald Trump of victory. Of course, that would have required plenty of voters being guided not just by their "true" first preference. The incentives to do so depended on what each voter expected other voters to do – both in Utah and in the rest of the United States.

As it turned out, Utah alone didn't matter in Electoral-College terms in 2016. And, in any case, depriving Trump of his Utah victory would have required near unanimous tactical voting by either all McMullin or all Clinton voters for a candidate who wasn't really their first choice.

But now, consider a state in which Trump is at 47.5%, Clinton at 47.3% and the third-placed candidate at 3.6%. That was the situation in Michigan, and the third-placed candidate was Libertarian Gary Johnson. In that instance, it is no longer so far-fetched to imagine just enough Johnson voters waking up the next morning with regret about having a share in handing Trump the presidency. The same could probably be said about some of the voters of Green-party candidate Jill Stein (1.1%), the already mentioned anti-Trump conservative McMullin (0.2%) and others (0.4%). That is not the full story of 2016 either, though. In five states, Clinton won with less than 50%, switching by third-party voters would have made all the difference there, too. For example, Clinton carried Minnesota with 46.4%, Trump was at 44.9% and Gary Johnson at 3.8%.

Such races are inherently less predictable. After all, whether to cast a vote against the perceived frontrunner partly depends on how certain you are the frontrunner will win. The less certain you are, the more tempting tactical voting becomes. In that sense, Trump probably benefitted from the perceived unlikelihood of his victory, and not just because this might have decreased turnout among Democratic voters. Based on Donald Trump's 2016 results, it is impossible to say whether he could have done so again the day after defying predictions on November 8, 2016, even when talking about the same voters turning out again on November 9.

In our view, part of the point of making good forecasts requires acknowledging such uncertainties. That starts with how to design scenarios to forecast and track. To be useful for those purposes, scenarios should be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive (MECE), if you will forgive a bit of jargon. Moreover, they should enable you to clearly assess whether the eventual outcome corresponds to the forecast or not.

In that sense, our initial, simple presidential-election scenarios (Trump, a Democratic nominee or someone else wins) are useful to us, because it covers all possibilities and will allow us to say in the end whether we got it right. For our more user-friendly outcomes a, b and c, introduced in Section 4, we tried to be MECE, too. But it's quite a bit harder, and requires putting a large range of diverse electoral outcomes in our Mushy-Middle class of cases (outcome "b").

Then, there is the small matter that markets might overestimate how much damage or good any candidate might do. Especially if his/her party does not control Congress, the impact any U.S. president can have on the U.S. economy and stock markets tends to be indirect, tangential and subject to time lags. That is one of the reasons why few previous presidents invoked stock-market highs as evidence of their success. It leaves an incumbent highly vulnerable if the market turns sour. That is one of the reasons why we think market faith in the so-called "Trump put"[25] beloved by pundits might well be tested in 2020.

Pundits have quite a bad reputation among forecasters. Part of their pitch is usually to have one or a few big ideas, conceptual models or core beliefs and apply them to any forecasting problem that comes along. If those forecasts fail to materialize, they tend to double down on their analysis, even in the face of mounting evidence that they might be wrong. Worse still, they might even avoid undertaking the sort of tests that risk proving a pet forecast wrong.

As the ground-breaking work by political psychologist Philipp Tetlock pointed out, this is precisely the opposite of what you should be doing to make good forecasts.[26] Based on a series of forecasting tournaments between 1984 and 2003, Tetlock tried to figure out two things. First, how good was the average political expert at making forecasts? And second, were some experts better forecasters than others?

The answers to both questions were quite surprising. It turned out that a vast number of well-paid experts were no better than an algorithm randomly assigning probabilities. Provocatively but perhaps unwisely, Tetlock described this finding as the average expert being no better at forecasting than a dart-throwing chimp. That rather detracted from his second, arguably more significant finding. Some experts were actually quite good, and they appeared to share certain cognitive characteristics.

Good forecasters tend to draw from a wide range of sources, have few preconceptions and are disciplined in keeping track of past forecasts, so that forecast accuracy improves over time. In other words, willing to change their mind as frequently as the evidence seems to suggest, but not too frequently.

Tetlock suspected that such mental habits are useful across a wide range of forecasting domains, that such traits could be learned and that combining solid forecasters into teams might boost performance even more. He summed up his results in a highly accessible book, published just in time for our 2016 electoral forecast which has been a source of inspiration within our team ever since. The book is called "Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction."[27] It remains highly recommended reading for anyone making predictions for a living, including those who manage other people's money. Hopefully, it will serve us and perhaps you well in 2020 and beyond. No matter who ends up winning in November 2020.

1. All historical data is based on the information released by the Federal Election Commission, available at: https://www.fec.gov/introduction-campaign-finance/election-and-voting-information/

2. See: https://www.dws.com/insights/cio-view/emea-en/our-us-election-watch-2016-09/?setLanguage=en; It is still well worth a read, especially on many of the longer-term structural trends we will not have space to cover in the present publication.

3. https://www.thedailybeast.com/for-us-presidents-odds-for-a-second-term-are-surprisingly-long?ref=scroll

4. A two-thirds majority of senators – 67 if everyone votes – voting to convict would be required to remove Trump from office.

5. See: https://www.dws.com/insights/cio-view/emea-en/us-midterm-elections-2018/?setLanguage=en; That too is still well worth a read, not least to give you an idea of how good our own forecasting record has been.

6. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-polls-arent-skewed-trump-really-is-losing-badly

7. To take one example of such hints, consider the 2019 UK general election. During the recent campaign, about one in five of Labour's voters failed to recall their previous voting decision correctly, when prompted by pollsters in recent months on how they had voted in 2017. Such conscious (or more likely unconscious) "buyer's remorse" offered an early, and, as it turns out, reliable indication of the larger-than-expected collapse in the Labour vote in many seats it had held for decades. For details, see: https://dws.com/insights/cio-view/cio-flash/cwf-2019/over-to-you-brussels/?setLanguage=en

8. https://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/29/poll-averages-have-no-history-of-consistent-partisan-bias/

9. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-polls-are-all-right/

10. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-state-of-the-polls-2019/

11. As already mentioned, Republicans currently hold 53 Senate seats. There are 45 Democratic Senators, plus two independent members of the Senate, Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Angus King of Maine, who caucus with the Democratic Party. Effectively that means that the chamber is split 47 vs. 53. Unless otherwise stated, our source for all Congressional seat counts and election results is https://ballotpedia.org, which has a wealth of useful data.

12. For example, in the 2012 and 2014 elections, Republicans received about 3.8% and 4.4% more House seats, respectively, than their national margins suggested. See: Trende, Sean: "The Myth of Democrats' 20-Million-Vote Majority," RealClearPolitics, as of 1/5/15

13. That same year Republicans won 199 House seats. You may have noticed that this does not add up to 435 seats. The reason is that results from one congressional district, North Carolina's 9th, were voided, after voting irregularities came to light. That led to a special election in September 2019, which the Republican candidate won.

14. For further details on the 2018 midterms, see: https://www.dws.com/insights/cio-view/emea-en/us-midterm-elections-2018/?setLanguage=en

15. Among the 43 governorships not up for re-election in 2020, for example, Democrats hold 23 and Republicans only 20.

16. The FiveThirtyEight Trump approval and disapproval tracker is available at: https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/trump-approval-ratings/?ex_cid=rrpromo

17. A lot can happen until November, and some of it may well end up favoring one of the more extreme scenarios. However, you would expect such game-changers to make themselves felt in the polls. A backlash against impeachment, for example, would most probably cut the current lead of 6.7% Democrats have in the congressional generic ballot. If Elections were held next Tuesday, the same polling on that measure alone would suggest a lower probability of Republicans regaining the House.

18. The Democratic National Convention takes place every four years in the summer before a presidential election, with the main purpose of confirming the Democratic candidate for president and vice president.

19. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/issues-voters-see-the-race-differently-from-those-who-prioritize-beating-trump/

20. See: Cohen, Marty et al. (2008): "The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform“, Chicago Studies in American Politics, University Of Chicago Press

21. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-polls-are-all-right/

22. https://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/09/29/poll-averages-have-no-history-of-consistent-partisan-bias/

23. In 2012, Obama won by 332 to Mitt Romney's 206 Electoral votes, incidentally also a much larger margin than Trump's 304 Electoral votes in 2016.

24. See: https://www.dws.com/insights/cio-view/emea-en/us-midterm-elections-2018/?setLanguage=en

25. The "Trump put" refers to the widespread belief that Trump, priding himself on the stock market's good performance since his inception, wouldn't let the market collapse

26. Tetlock, Philipp (2005): “Expert Political Judgement: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?”, Princeton University Press

27. Gardner, Dan and Tetlock, Phillip (2015): “Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction”, Crown