- The four D's (demographics, decarbonization, digitalization and deglobalization) are often cited as the reason why the inflation rate in advanced economies will remain elevated in the long term.

- This argument overlooks the influence of monetary policy. Central banks will not abandon their 2% target.

- However, we will probably have to live with missed targets for a while.

1 / The long-term drivers of inflation

1.1 The usual suspects: Demographics, decarbonization, digitalization and deglobalization

Only a few months ago, inflation rates in Western countries passed their zenith and have been falling more or less continuously ever since. However, core inflation is showing a worrying degree of persistence. In both the U.S. and the euro area it still exceeds 5% year-on-year. This increasingly raises the question of whether inflation will fall back to the target of 2% again in the foreseeable future or whether there are structural drivers that will keep inflation persistently on a higher level. The D's (demographics, decarbonization, digitalization, deglobalization) are being used to justify why inflation should remain at 3, 4, or more percent for many years to come.

We have our reservations about this view. First, the impact of these drivers seems to be overestimated; in some cases, it is not even clear whether the correlation is positive or negative. Second, these drivers only explain why individual (relative) prices have to change. They do not explain why all prices – the inflation index as a whole – should rise faster than in the past, which is what higher inflation is all about. In our view, though structural forces of various kinds are at play, monetary policy has the power to contain inflation.

1.2 Monetary Policy, Fiscal and Financial Dominance

Many of the analyses that focus on structural inflationary forces ignore the influence of monetary policy on inflation. After all, according to Milton Friedman, inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. We therefore contrast the four D's with an M (monetary policy). However, this raises the legitimate question of whether monetary policy can act as decisively as it would like to, given the high indebtedness of governments and banks. In other words, whether fiscal or financial dominance stands in the way of fighting inflation. That would be a fifth D: debt.

In the following sections, we will take a closer look at the drivers just mentioned and provide a view on how we expect the trajectory of inflation to play out.

2 / Demographics

2.1 Labor shortages and wage pressure

Demographic trends are frequently cited in the current debate on inflation. At first, the argument that they are behind the rise in inflation sounds very tempting. With the retirement of the baby boomers from working life and the entry of much more sparse cohorts of younger workers into the labor market, the working-age population is shrinking - either in absolute terms, as in large parts of Europe or Asia, or in relative terms, as in the U.S. This aging process is having a twofold impact: First, due to increased life expectancy, the proportion of old people in society is rising. They no longer work but of course continue to consume. Secondly, with increasing age, consumption is shifting more and more toward services, which cannot be imported and have to be produced in the country itself. The constant, or even increasing, demand for labor coupled with declining labor supply puts workers in a better bargaining position and, the theory goes, should therefore lead to rising wages.

This argument may seem convincing, but it overlooks important economic relationships. When fewer people work, their marginal value product rises due to the more abundant capital endowment. This means that higher wages can then also be justified by productivity gains. A higher wage share due to declining employment is not very plausible anyway. If the elasticity of substitution between labor and capital is constant, the aggregate wage share should remain constant. This can be well demonstrated empirically over (very) long periods of time.

2.2. Economic dynamism and the need for price adjustment

There is another argument for the inflation-dampening effect of demographic developments: aging (and, even more so, old) societies are less dynamic. GDP growth per capita need not be lower than in other countries, but the ability to innovate and adapt decreases with age. When there is less innovation, there are fewer relative prices to adjust. High inflation rates are usually found in countries that are developing dynamically. GDP growth and inflation rates are usually positively correlated.[1]

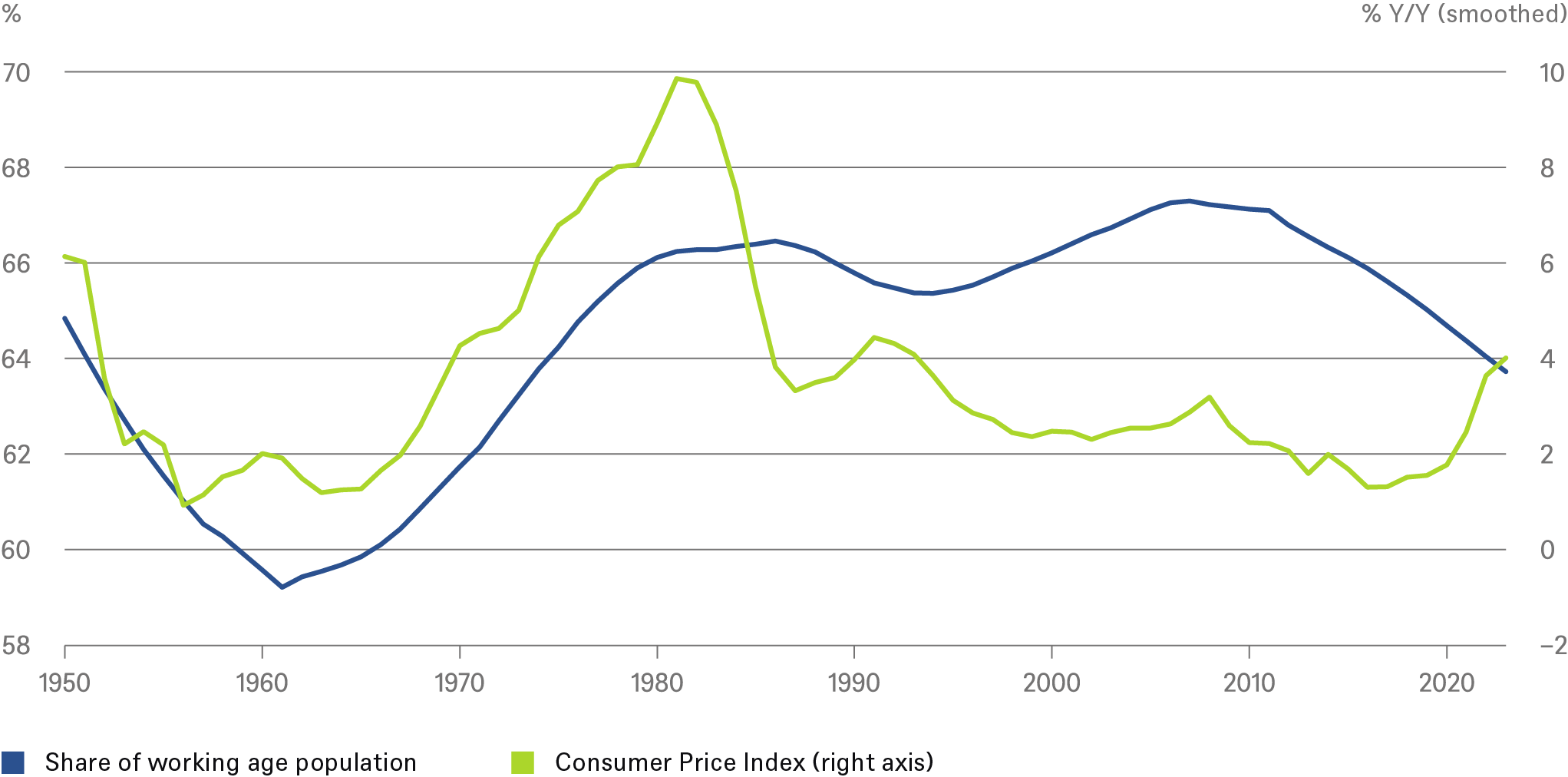

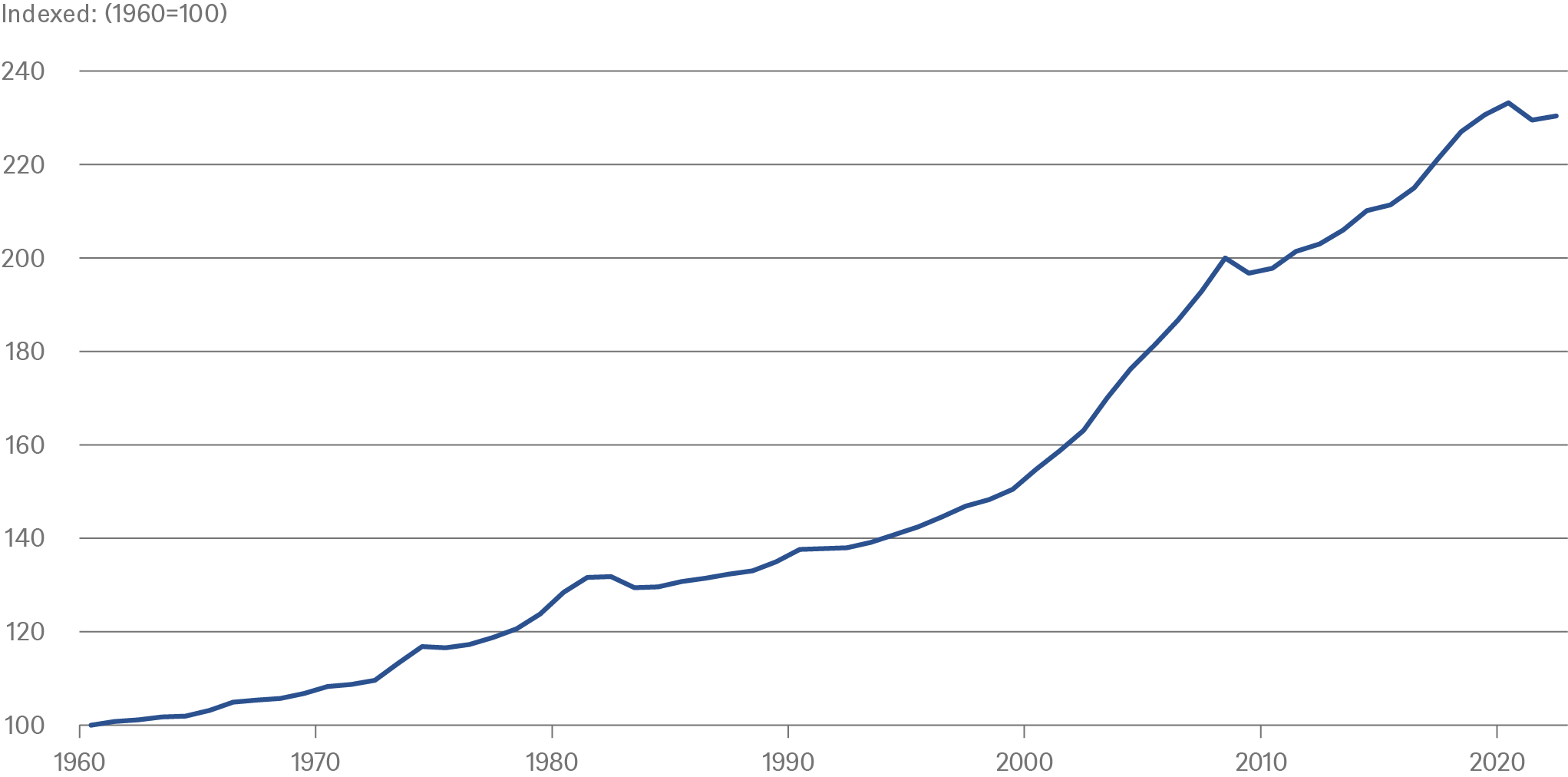

It is difficult to judge which demographic effect predominates. The empirical evidence is mixed. In Chart 1, for example, one sees that over long periods of time, increases in active populations have been accompanied by increases in inflation rates. The claim that declining demographics are a clear driver of higher inflation cannot be sustained empirically.[2]

Chart 1 U.S.: Demography and inflation - aging as inflation brake or driver?

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Haver Analytics Inc., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Haver Analytics Inc., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

3 / Decarbonization

Here, the situation is clearer. Both climate change itself and the fight against it are clearly driving up many prices. Climate change is making it necessary to adapt production in many respects; and companies can pass on the associated costs of doing this to customers in the form of price increases. Last summer, for example, prolonged drought caused the levels in French rivers to drop so low that quite a few nuclear power plants, which require large amounts of water for cooling, had to stop producing electricity. This, together with the rise in gas prices due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, has driven European electricity prices to astronomical heights.

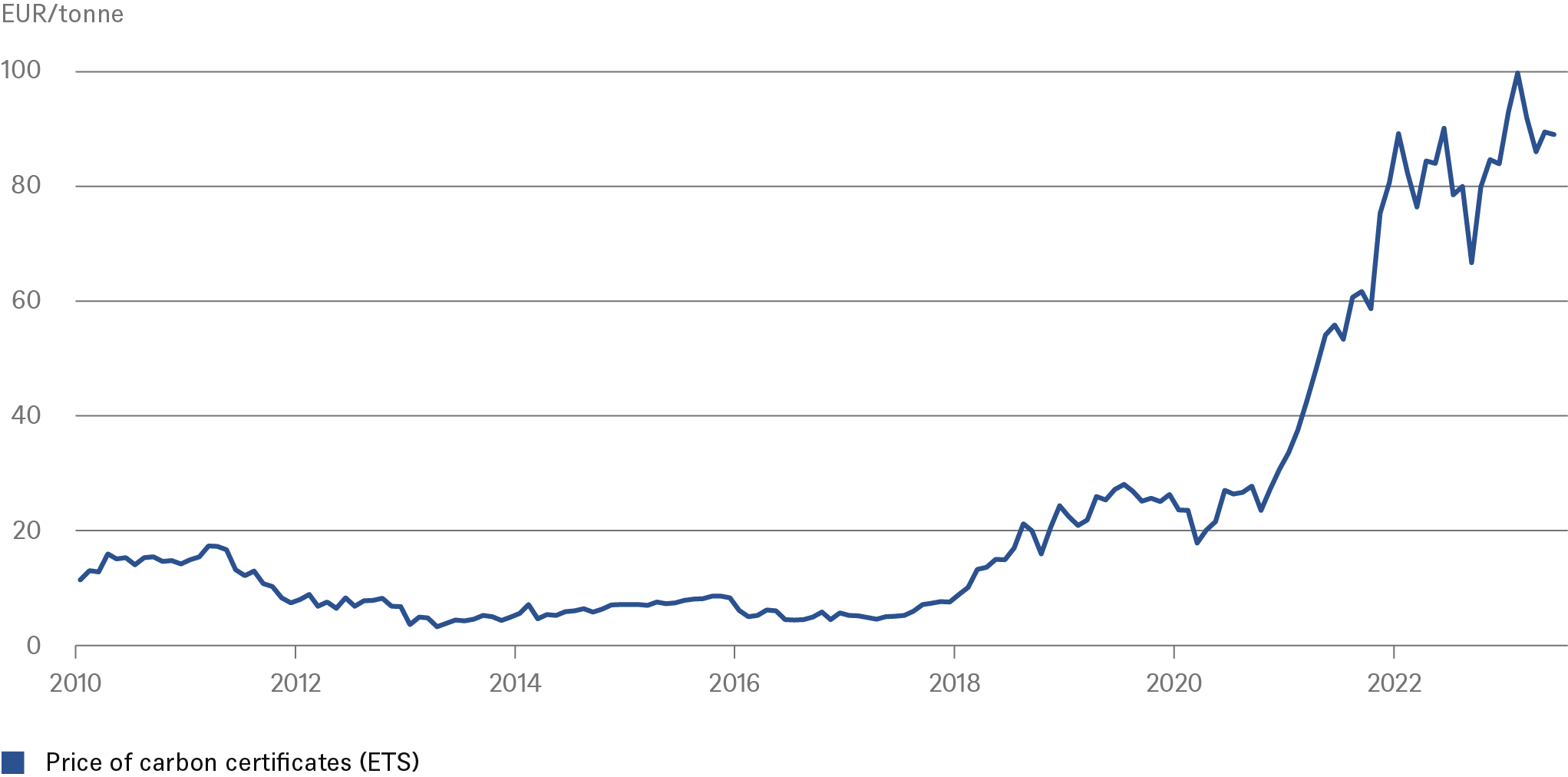

At present, however, the costs for companies of the fight against climate change are far higher than the costs of climate change itself. In the last five years the price of carbon in the EU has increased more than tenfold (Chart 2). In addition, more and more emitters of carbon have to purchase the corresponding certificates. And this is certainly not the end of the story. If the economy is to be made climate neutral, further increases in the cost of carbon emissions are unavoidable.[3] Basically, carbon emissions must become so expensive that they are no longer worthwhile. If bans on carbon emissions are also used to achieve climate neutrality, these too will give an impulse to prices.

Chart 2 European Union: Carbon allowances – sharp rise in prices

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

Sources: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

4 / Digitalization

Recently, digitalization has also been widely cited as a reason for rising prices. This is surprising, because just a few years ago it was considered one of the main drivers of falling prices.

Essentially digitalization gathers together other trends, such as automation and, more recently, artificial intelligence. All of these new developments contribute to more efficient and therefore more cost-effective production. Digitalization also intensifies competition for many non-digital products, for example, by making it easier to compare prices, while online retailing makes expensive store locations superfluous, etc.

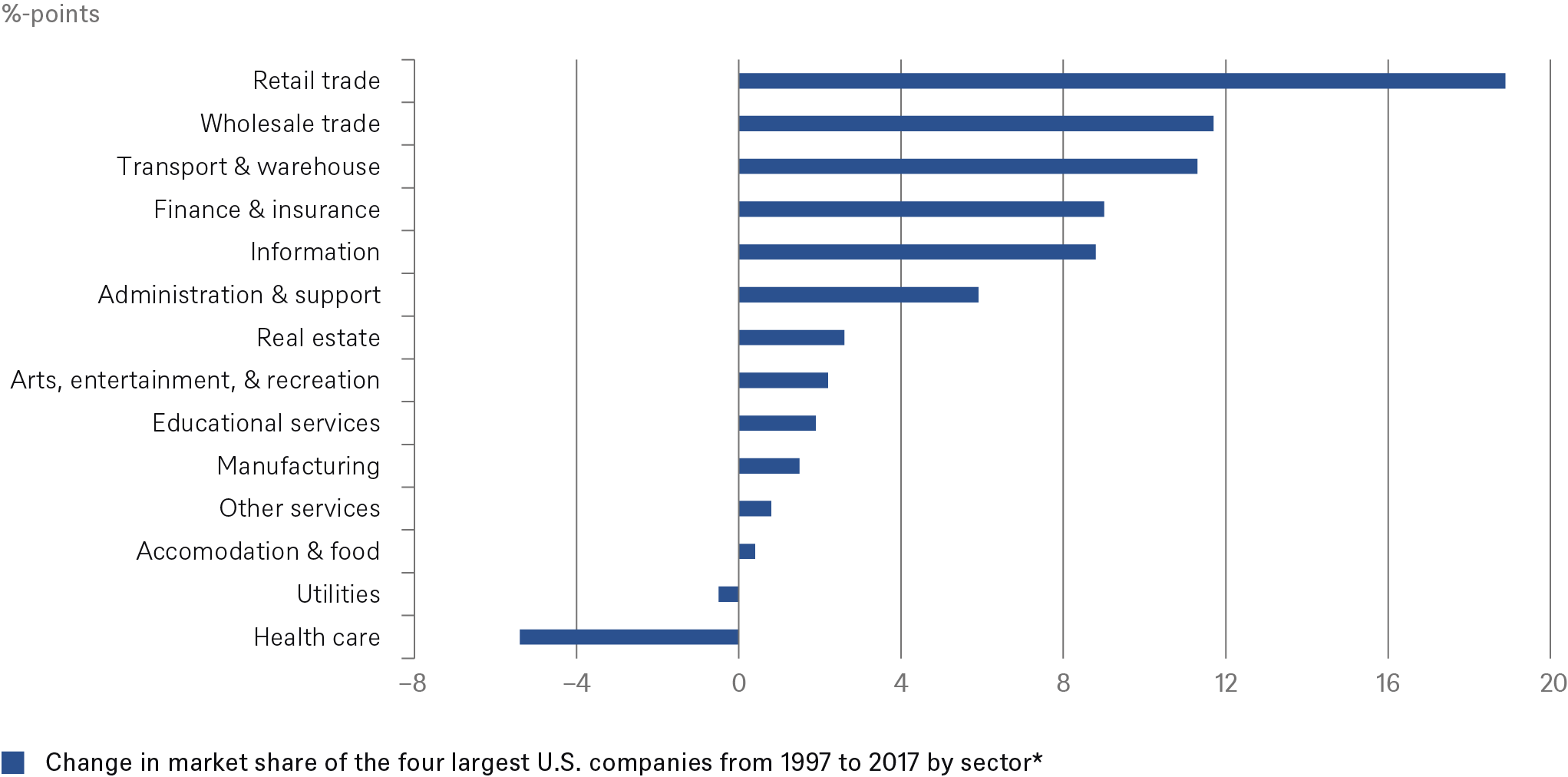

But what all these drivers have in common is that they boost market concentration. The underlying economics of superstars (benefiting from no or low marginal costs of production and network effects) mean that everyone wants to use the products of the market leader (“the winner takes it all”). In fact, market concentration in the U.S. has increased strongly over the last twenty years (Chart 3). The fear is that corporations could exploit their quasi-monopoly position to raise prices. In the case of AI, this could even go a step further. What happens if AI recognizes that price collusion is advantageous for the companies involved? In the long term, then, it is quite conceivable that the market concentration and market power enjoyed by the companies involved in automation, digitalization and AI will lead to rising prices. But then regulation must be used to deal with these oligopolistic structures. At present, however, the impression is that there is growing awareness of these risks but that robust intervention is still a long way off. Thomas Philippon (2019), a professor of Finance at the New York University, argues that U.S regulation has fallen behind the EU’s.

Chart 3 U.S.: Market concentration – the winner takes it (almost) all

* Change in sales-weighted mean of 6-digit industries. Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), DWS Investment GmbH as of 07/04/23

* Change in sales-weighted mean of 6-digit industries. Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), DWS Investment GmbH as of 07/04/23

5 / Deglobalization

Deglobalization is also increasingly being blamed as a driver of inflation. However, this is a complex question for several reasons. It is not clear that deglobalization is really taking place. Nor is it clear to what extent its opposite, globalization, actually had a dampening effect on prices. These uncertainties stem from the fact that trends in globalization and, if it is occurring, deglobalization have certainly been accompanied and perhaps overshadowed by other developments. Globalization’s triumph was accompanied by that of a stability-oriented monetary policy. Perhaps monetary policy, rather than globalization, was primarily responsible for falling prices.

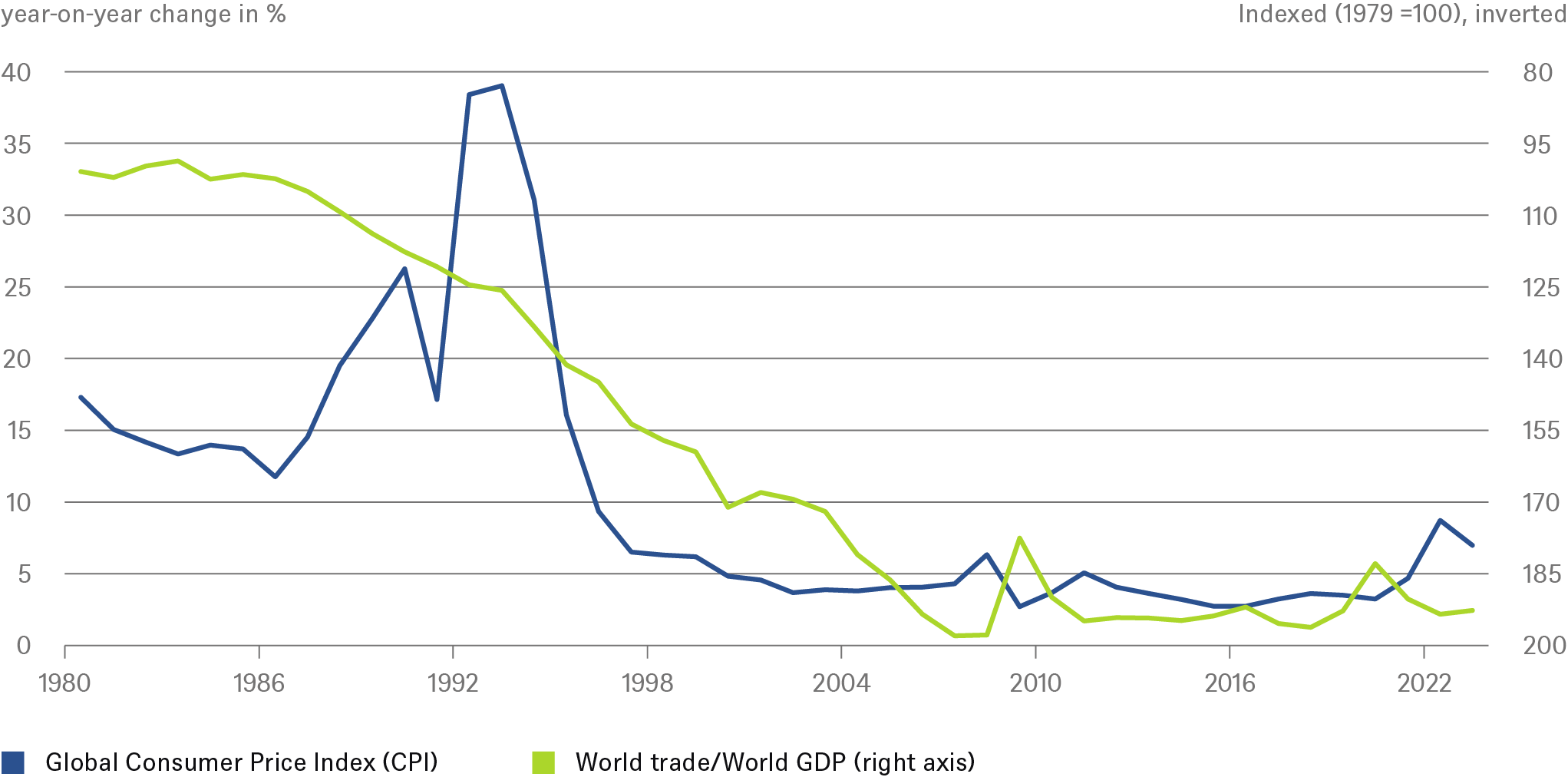

There can be no doubt that since the 1980s, globalization has steadily advanced. World trade grew faster than world GDP. Goods and also services, to the extent that they are tradable, are increasingly produced where it is relatively cheapest to do so. This has unquestionably had a favorable impact on goods prices. The continuous fall in the price of color televisions in the U.S. is just one example of this. But wage restraint in Germany at the beginning of the 2000s can also be attributed, at least in part, to a wave of outsourcing by German companies.

Chart 4 Global trade and inflation – globalization as a price brake?

Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF), Haver Analytics Inc., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF), Haver Analytics Inc., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

However, Chart 4 also shows the limits of this relationship. The global inflation rate continued to rise until the mid-1990s, even though globalization was already making rapid progress, and global consumer prices had already stabilized by the turn of the millennium - long before the peak of globalization. This also explains why scientific studies repeatedly come to the conclusion that globalization - surprisingly for many laymen - has contributed only a small share to disinflation.[4] However, it has very much contributed to a synchronization of inflation rates in developed economies.[5]

The current extremely high inflation rates are primarily due to supply chain difficulties resulting from the Covid pandemic and should not be confused with deglobalization.[6] Nevertheless, globalization has probably long since passed its peak. Whether you call it friendshoring, nearshoring, supply chain risk diversification, or regionalization, free trade is in retreat. Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, the suspension of negotiations on numerous free trade agreements, the virtual death of the World Trade Organization - all of these are eloquent witnesses to rampant protectionism. This is likely to mean that globalization will advance less in future and therefore not bring major fresh benefits. But globalization will not be completely unwound. And its influence on inflation in the past was not as strong as is generally thought.

6 / Monetary policy

A preliminary conclusion might be that some drivers, such as demographics and digitalization, have an ambivalent influence on inflation. In the case of deglobalization, as we have argued, the influence is probably not so pronounced. The effect of decarbonization is clearer: it is increasing prices. But, and this is our central argument, all this implies only a shift in relative prices, not that prices as a whole will increase faster than in the past.

Chart 5 shows the relative price development of services (excluding energy) compared to the overall inflation index. Services have risen much more than overall inflation. It is therefore possible for individual groups of prices to rise significantly more than others over a long period of time without permanently raising the overall inflation rate. That inflation has receded since the 1970s is likely to reflect the influence of monetary policy. As already mentioned in the previous section, stability-oriented monetary policy in the U.S. began toward the end of the 1970s, at the latest when Paul Volcker took office as Federal Reserve Chairman.

Chart 5 U.S.: Service prices in relation to total price index

Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF), Haver Analytics Inc., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF), Haver Analytics Inc., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

In the case of high inflation, monetary policy can basically only weaken the demand side (via higher lending rates) and thus ensure that supply and demand are matched again. If the central bank raises interest rates, real estate loans become more expensive, households have less money for consumption, construction activity suffers, and corporate demand for capital goods also declines as a result of higher investment costs. This even has the counteracting effect that monetary policy weakens the supply side and therefore the inflation-dampening effect of interest rate hikes. Rents, which account for a relatively high share of total household spending, may also rise, partly because less housing is built and partly because financing costs are rising.

It takes time for this weakening of demand to take effect. The more companies and private households have taken precautions and loans with long maturities, the longer it will take for high interest rates to have a broad impact. At present, high wage increases are also ensuring that core inflation will certainly remain high for quite some time. Wage rises boost demand in the economy as a whole.

This Special is about the extent to which structural drivers will permanently raise the inflation rate. These drivers, the four D's, certainly mean that many relative prices will have to adjust. But central banks are not responsible for relative price changes; they are responsible for the overall price level, or more precisely, the level of inflation. Ultimately, how much inflation central banks should tolerate is a societal question. Society might see decarbonization as a "good cause" for inflation but the central banks have made clear that they do not want to sacrifice their inflation target.[7] The 2% inflation target remains the holy grail of central banks.

7 / Debt

Another question, however, is the extent to which central banks can achieve what they want and reach their low inflation grail. A factor that some believe makes that unlikely goes under the heading of “fiscal dominance” and - somewhat less commonly – “financial dominance”.

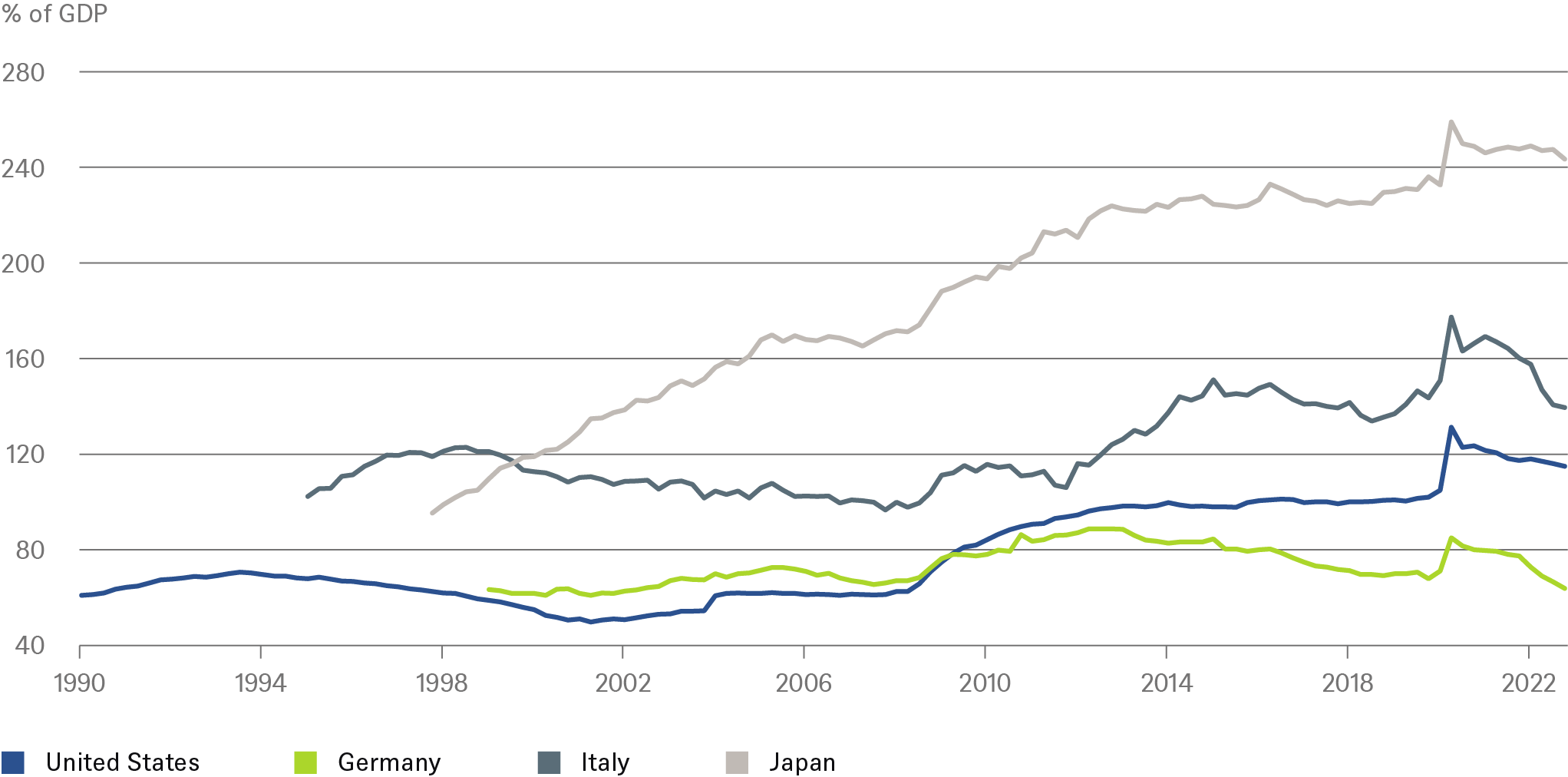

“Fiscal dominance” raises the question of whether government debt has reached such heights that central banks cannot raise interest rates to the necessary level because otherwise nations would go bust. Of course, such considerations always play a role in central banks’ thinking. For example, the European Central Bank (ECB) introduced the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) specifically to ensure that “fundamentally unjustified” spread widening does not occur. As controversial as the instrument may be in theory, it has served its purpose so far. Sovereign governments are by and large coping well with the rise in interest rates at the moment. It takes time, however, for high interest rates to affect government budgets. Sovereign debt usually has long maturities, and the interest rate level ten years ago, when much of the debt now maturing was taken out, was not so far from the current one.

Chart 6 Global increase in government debt

Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF), Haver Analytics Inc., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF), Haver Analytics Inc., DWS Investment GmbH as of 7/04/23

“Financial dominance” raises the question of whether banks are in such a precarious situation that central banks are constrained in their monetary policy. Again, for a central bank, such considerations always play a role, not entirely without reason, as the recent difficulties at some regional banks in the U.S. show. But a central bank has more than one tool at its disposal. The numerous measures initiated by the Fed in connection with the insolvency of Silicon Valley Bank have - at least so far - successfully prevented further bank failures. In addition, banks have cleaned up their balance sheets in the aftermath of the financial crisis and strengthened risk management and risk provisioning.

Interest rate hikes generally have an asynchronous effect: They arrive quickly in the financial and insurance sector, but only begin to brake the economy as a whole after some delay. However, the currently high debt levels of the private nonfinancial sector (companies and households) ensure that even lower interest rate hikes than in the past will have a dampening effect on demand. Both fiscal and financial dominance are likely to play a certain role in the central banks' deliberations, but their role will not be a determinant.

8 / Conclusion and outlook

What does all this mean for the inflation outlook in the coming years?

First of all, we firmly believe that central banks will stick to their 2% target. Anything else would radically undermine their credibility, the most valuable asset of central banks.

Nevertheless, we doubt that the central banks will achieve their target quickly. The after-effects of the pandemic on the labor and goods markets, and the sharp rise in wages and the resulting demand from that, should all mean that inflation rates fall only slowly.

However, we reject the idea that the central banks will not be able to achieve their inflation targets even in the long term due to the four structural drivers. It is unclear whether demographics are inflationary or if digitalization is disinflationary. Deglobalization and decarbonization are clearly inflationary, but the extent of deglobalization and its effect on inflation is likely to be rather small, and decarbonization mainly affects a few relative prices. Whether inflation, i.e., a continuous rise in the price level, follows from this depends on the central banks - perhaps even more than in the past. When the Western world, led by Europe, suffered from excessively low inflation rates and there was concern - well-founded or not - that individual economies might slide into deflation, it was indeed difficult for central banks to achieve their goals, since they basically had no tool to fuel inflation.

Concerns about deflation are off the table - the four D's should see to that - and the central banks do have effective tools to fight inflation. If the central banks do not want to lose their credibility, they cannot give inflation free rein. Given the difficulties created by high national debts, climate targets, supply-side legacies of the Pandemic and the war in Ukraine, one can well imagine that the central banks will see it as a success in the future if the inflation rate has a 2 before the decimal point. Average inflation rates of 2.5% in coming years look quite realistic. But we believe the central banks will not be satisfied with inflation rates of 3 to 4% in the long term and won’t be deterred by talk of the four D’s from pursuing their low inflation grail.