Lately, some news headlines have been truly remarkable: “Major Japanese firms agree to hefty wage hikes”[1], what makes it remarkable is that it contains the word “Japan”. Since the mid-1990s, "Japanification" has become shorthand for a supposedly perennial economic malaise that other rich but rapidly aging countries may face in the coming decades.

This year’s spring wage talks (Shunto) between unions and Japan's leading firms are putting such ideas to the test. Strictly speaking, most actual wage negotiations take place at the enterprise unions or between company groups and their unions, rather than at the level of industries. Traditionally, Shunto has mainly been a way to facilitate coordination. Having pay talks take place roughly simultaneously according to some predetermined sequence first emerged during the post-war boom years to contain wage leapfrogging[2].

.

Accelerating wage growth already, if you squint

indexed: 12/31/90 = 100% of GDP

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., DWS Investment as of 3/7/23

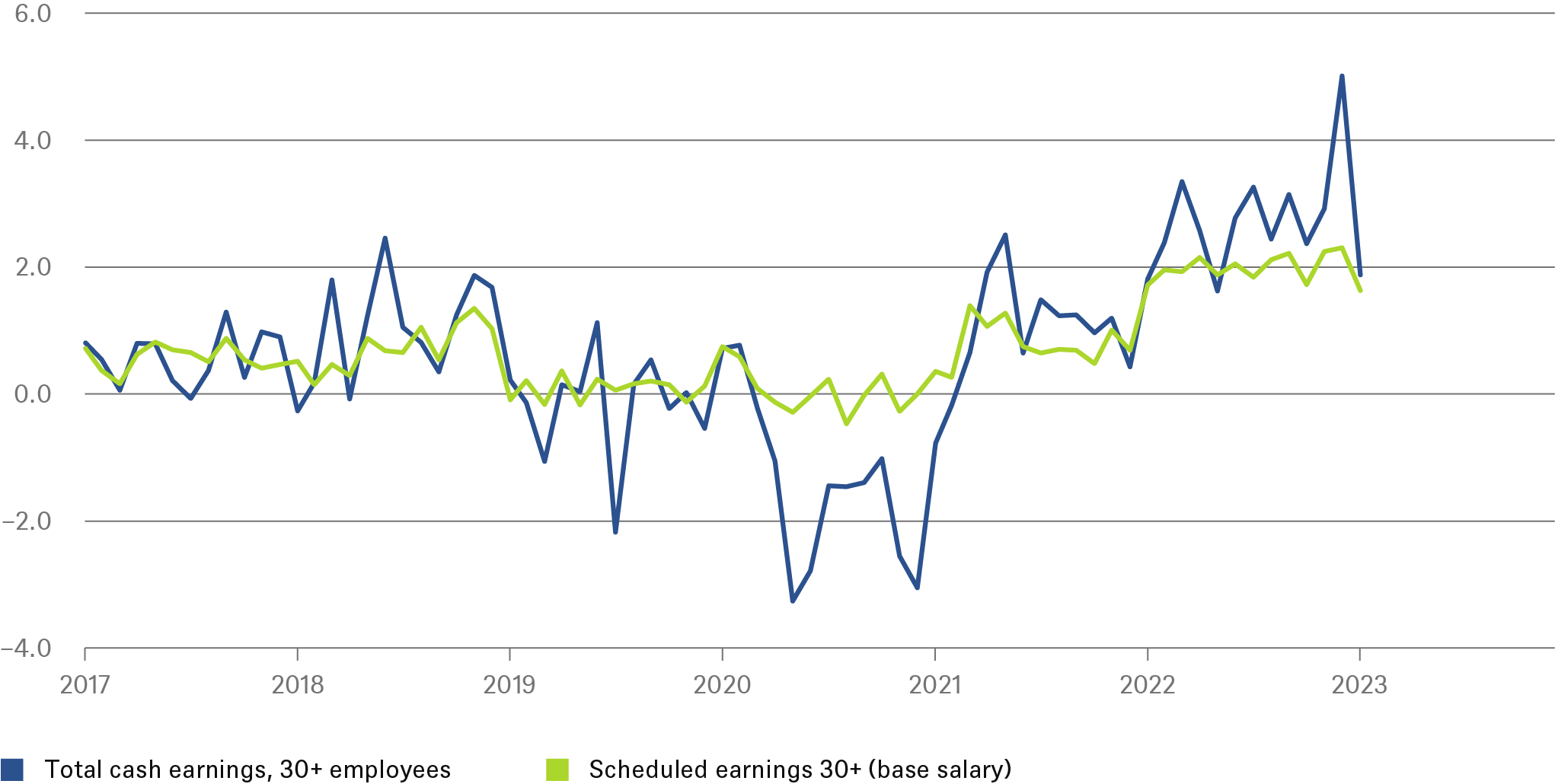

Over the past decade, Japanese policymakers have instead been eagerly hoping for what they would see as a “virtuous cycle between wages and prices”, that is a combination of rising prices and higher wages. There has been much debate over precisely why the legacy of debt crises that took place in the 1990s has led to sluggish growth and low or no inflation for over thirty years, despite increasingly expansive monetary and fiscal policies[3]. Shunto relies heavily on informal as well as formal information exchanges between enterprise unions and employee’s representatives, as well as the government. The government has made its preferences for wage rises of 3% or above clear. Given productivity trends and seniority-based salary gains to the amount of around 1.7% p.a. for those Japanese workers still enjoying life-time employment, that might be roughly be consistent with finally coming close to the 2% inflation target. But only if settlements for large enterprises also starting setting the tone for employees' pay at non-unionized smaller firms. Already, wage growth appears to have accelerated even before the current Shunto.

For now, we think that the Bank of Japan (BoJ), which is coming under new leadership will probably wait for firm evidence of sustained, economy-wide wage gains. Any BoJ pivot towards a normalization course would have significant implications for global equities, bonds and currency markets, given the size of Japanese investment flows[4].

There is another reason to keep a close eye on those Shunto talks. For many years now, "Japanification" has been used to "explain" episodes of low inflation and interest rates in other aging economies. Look closely and there is always more involved than just aging. Indeed, the first example of "Japanification" was arguably the Great Depression, when populations were still young and growing. For several years, some observers have pointed out the many ways in which Japan’s experience might be misleading[5]. One aspect appears especially relevant. Because of cultural, political, and language barriers, the Japanese labor market has long been unusually isolated. But given just how low entry-level Japanese wages now are compared to other rich countries, more and more young Japanese are trying to escape abroad. Already, it is becoming clearer and clearer that "Japanification" is not what it used to be.